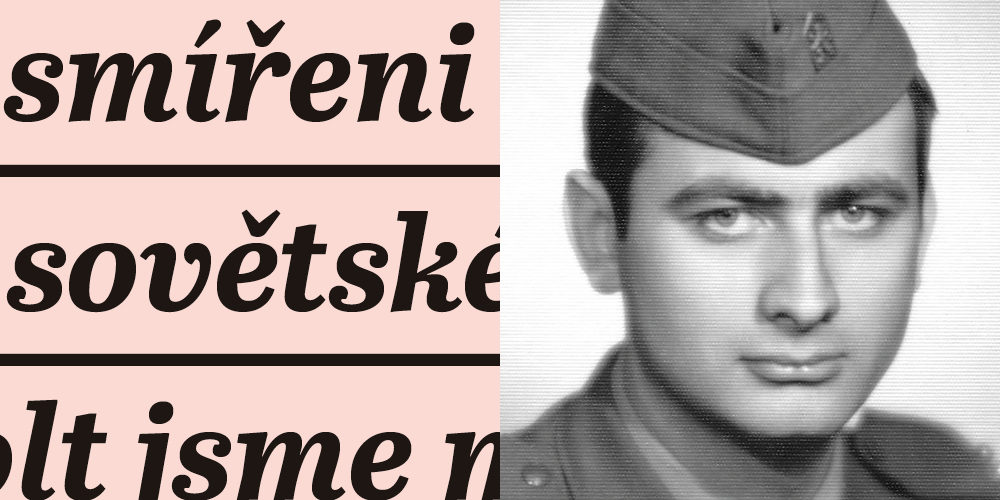

In August 1968, Jaromír Ulč had no idea that he was about to embark on a long career with the state security. He was not interested in politics. “I didn’t think anything of it, we didn’t talk about it at home,” he says of the invasion by Warsaw Pact troops. Like many in those days, he wore a tricolor in his lapel. But when Soviet soldiers stopped him on a bridge over the Vltava River, he dutifully unbuttoned it: “I had to throw it into the river myself,” he said.

He later joined the communist Ministry of the Interior. At first, he eavesdropped on Western border guards and diplomats, and later, as a counterintelligence operative, he was in charge of monitoring churches. The presence of occupying troops in Czechoslovakia was a given for him, which he did not question.

“We are a small country in the middle of Europe, which has to belong somewhere. We were resigned to being in the Soviet Bloc. We didn’t compare too much whether the West was better or worse,” he said. And in the same breath, he mentioned the advantages it brought him:

“The way I perceived the regime was that I had decent money, my family was taken care of, I had a place to live, and I was more or less not bound by anything, that I could do whatever I wanted, even if not completely. That’s the way it is, maybe that’s the way it has to be. I’m no rebel, nobody in my family was a rebel.”

Surveillance

After February 1948, the communists, following the Soviet model, eliminated civil liberties. They stole from everyone who owned land or other property. They imprisoned thousands of people in labor camps, where many mined uranium ore for the Soviet Union in inhumane conditions. Hundreds of those who were inconvenient were murdered or sentenced to death and executed by the communists (Píka, Horáková, Broj, Slánský, and others). They isolated the country from the free world and introduced censorship. Not everyone surrendered. Brave people founded resistance groups and smuggled refugees across the border. They resisted the incipient totalitarianism with words and deeds.

But it did not start on 25 February 1948. The Communist Party, strengthened by the authority of the Soviet Union with the halo of the “liberator from Nazism,” had already become a political hegemony, as it confirmed by winning the semi-free elections in 1946. The comrades were lying then when they assured voters that they would not go the Soviet way, that “there will be no collective farms in our country.” After the February coup they declared that “the will of the ruling class is above the law.” And this will of the workers was “represented” by the Communist Party. For forty long years the country submitted to the will of the leaders of the Soviet Union. The Communist Party was subject to directives from Moscow on fundamental issues. Soviet advisers oversaw the course of fabricated show trials. However, none of this removes the main responsibility from the domestic actors for the widespread crimes that characterized the domestic totalitarian system.