“Travel to the Soviet Union is not recommended,” read the catalog of the Urania travel agency, which Hana read as a little girl before the war.

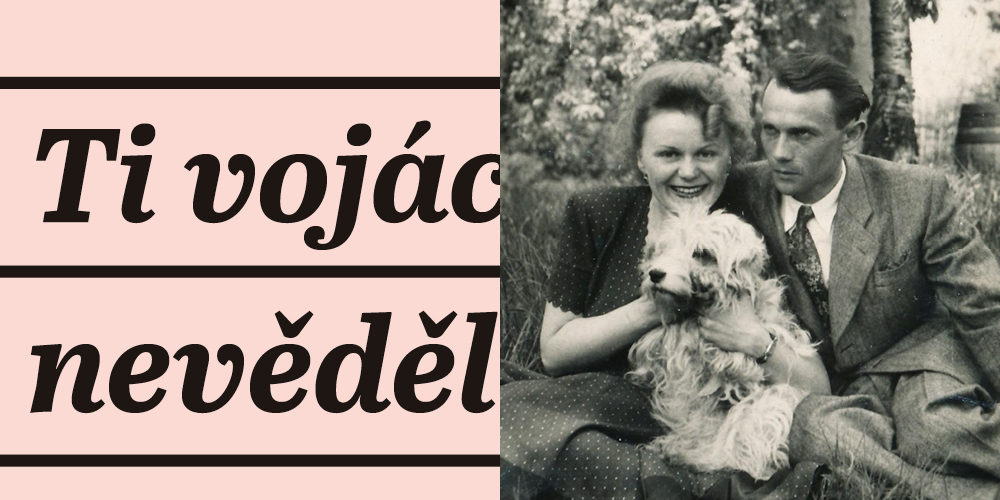

She grew up in Teplice, which became part of Hitler’s Germany after the Munich dictatorship. When the Soviet soldiers arrived here on the night of 8-9 May 1945, they behaved as if they were in enemy territory. “The borderlands experienced the end of the war in a drastic way. The soldiers did not even know exactly where they were. They possibly did not even have maps with them. They thought they were in Germany,” recalls Hana Truncová, née Johnová. The soldiers behaved with brutality to match:

“They took people’s bicycles, they took watches off their wrists, they tore crosses from their necks. Everything you can imagine. By what right?”

A year later came the first post-war and, as Hana says, “so-called free,” elections. “Everything in the whole border region was covered only in red. Voters were almost afraid to vote for anyone other than the communists. Many citizens were given a house, an apartment, the various necessities of life. So, they went to the polls to say thanks. Yes, that was the beginning of the end.”

After the coup in February 1948, Hana considered emigrating. Before she and her beloved Otakar Čeňek Trunc decided to do so, they were arrested by StB officers in the summer of 1951. Hana was sentenced to 13 years for treason. She ended up spending nine years in communist prisons.

Surveillance

After February 1948, the communists, following the Soviet model, eliminated civil liberties. They stole from everyone who owned land or other property. They imprisoned thousands of people in labor camps, where many mined uranium ore for the Soviet Union in inhumane conditions. Hundreds of those who were inconvenient were murdered or sentenced to death and executed by the communists (Píka, Horáková, Broj, Slánský, and others). They isolated the country from the free world and introduced censorship. Not everyone surrendered. Brave people founded resistance groups and smuggled refugees across the border. They resisted the incipient totalitarianism with words and deeds.

But it did not start on 25 February 1948. The Communist Party, strengthened by the authority of the Soviet Union with the halo of the “liberator from Nazism,” had already become a political hegemony, as it confirmed by winning the semi-free elections in 1946. The comrades were lying then when they assured voters that they would not go the Soviet way, that “there will be no collective farms in our country.” After the February coup they declared that “the will of the ruling class is above the law.” And this will of the workers was “represented” by the Communist Party. For forty long years the country submitted to the will of the leaders of the Soviet Union. The Communist Party was subject to directives from Moscow on fundamental issues. Soviet advisers oversaw the course of fabricated show trials. However, none of this removes the main responsibility from the domestic actors for the widespread crimes that characterized the domestic totalitarian system.