“They stripped me naked, beat me unconscious, I was swollen everywhere. A guard stood over me with a bucket of water. Only that bucket of water woke me up.”

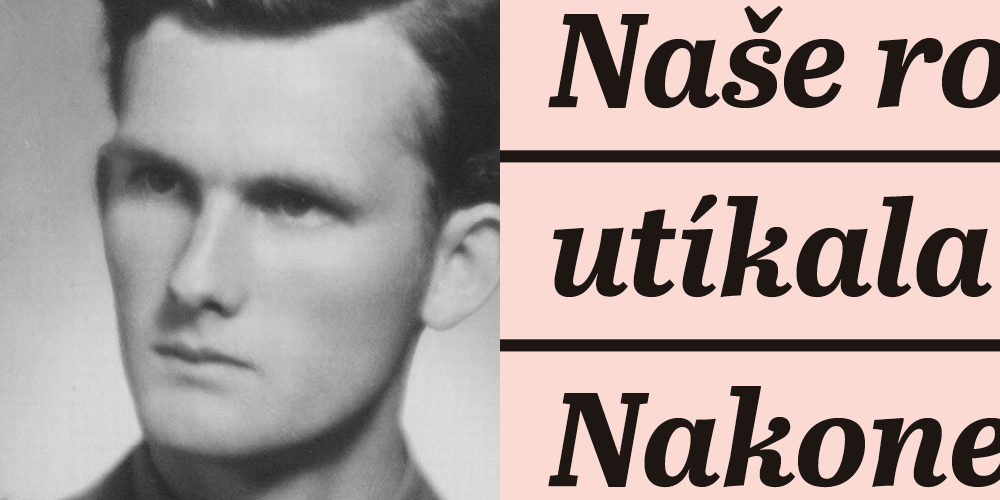

This is how Julián Slepecký describes his interrogation following his capture in 1951 after an unsuccessful attempt to escape from communist Czechoslovakia.

The son of a Ukrainian father and a Czech mother, Julián was born in Halych in what was then Polish territory. His father, a veteran of the First World War, had experience fighting the Bolsheviks, and when Hitler and Stalin partitioned Poland in September 1939, the family struggled to survive the shifting fronts and attendant regime changes in the seclusion of the countryside.

The Nazis dragged Julian off to do forced labor in 1944, and after the war he found himself in a concentration camp for Soviet citizens in France. “There they told us that Comrade Stalin had given orders that all Soviet citizens abroad must be brought home.” During a stop on a transport train in Poland, Julian escaped and was reunited with his parents in Prague at the end of 1945. Just as they had promised each other during the war.

He became a soldier by profession and, as a staff sergeant, taught in a non-commissioned officers’ school. But he did not escape the dreaded Bolsheviks. After the Communist takeover in February 1948, he was disgusted by the transformation of the army along Soviet lines. Because of his failed attempt to emigrate, the court gave him a 20-year sentence. In 1959, Julian’s wife applied for his parole and succeeded. “There is good and evil in the world. I chose to fight for good and I that I did,” he says.

Surveillance

After February 1948, the communists, following the Soviet model, eliminated civil liberties. They stole from everyone who owned land or other property. They imprisoned thousands of people in labor camps, where many mined uranium ore for the Soviet Union in inhumane conditions. Hundreds of those who were inconvenient were murdered or sentenced to death and executed by the communists (Píka, Horáková, Broj, Slánský, and others). They isolated the country from the free world and introduced censorship. Not everyone surrendered. Brave people founded resistance groups and smuggled refugees across the border. They resisted the incipient totalitarianism with words and deeds.

But it did not start on 25 February 1948. The Communist Party, strengthened by the authority of the Soviet Union with the halo of the “liberator from Nazism,” had already become a political hegemony, as it confirmed by winning the semi-free elections in 1946. The comrades were lying then when they assured voters that they would not go the Soviet way, that “there will be no collective farms in our country.” After the February coup they declared that “the will of the ruling class is above the law.” And this will of the workers was “represented” by the Communist Party. For forty long years the country submitted to the will of the leaders of the Soviet Union. The Communist Party was subject to directives from Moscow on fundamental issues. Soviet advisers oversaw the course of fabricated show trials. However, none of this removes the main responsibility from the domestic actors for the widespread crimes that characterized the domestic totalitarian system.