“Pretend you’re deaf and dumb,” Natálie Laštovičková ordered her uncle Alyosha before they got into the taxi.

Her uncle had arrived in Prague by train for a long-planned visit from Sochi. His compatriots had arrived in Czechoslovakia, just a few days prior, but unlike her uncle, no one had welcomed them. It was August 1968. Prague’s main railway station was full of people fleeing to the West, the taxi driver was swearing at the “Russians,” the bus was buzzing like a beehive. Natálie had lived in Czechoslovakia since birth and her Czech was perfect, so the taxi driver did not recognize in her or her silent companion the fellow tribesmen of the hated occupiers.

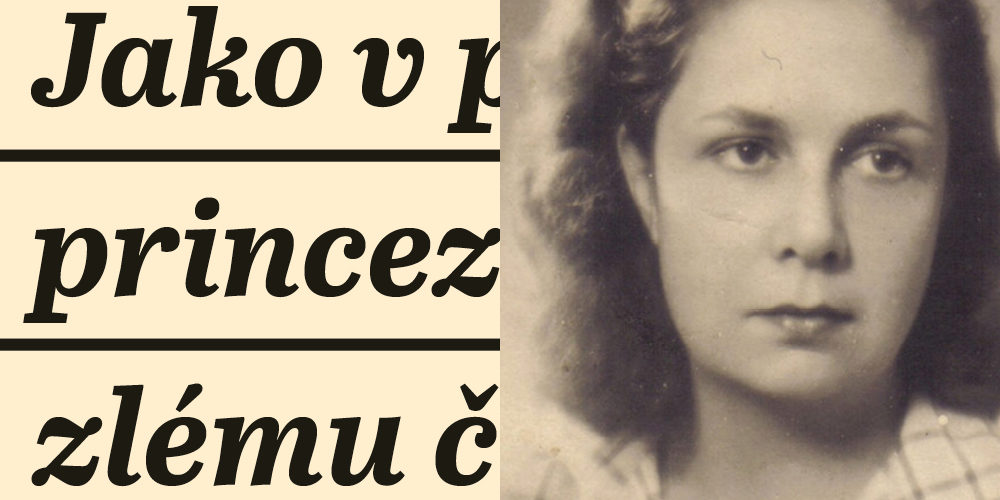

Natálie was born to Russian parents in Uzhhorod. After the Hungarian occupation of Subcarpathian Rus, they made the difficult journey to Prague as Czechoslovak citizens. At the end of the war, his father Yevgeny Kuftin helped the Soviet partisans and, perhaps thanks to that, the family avoided forced repatriation to the USSR. They remained in Prague but retained their Soviet citizenship.

Natálie never joined the Youth Union or the Communist Party, and made her living as an interpreter and translator. She visited the land of her ancestors several times. She always took with her several suitcases of things for relatives decimated by the regime. Ambivalence between love for her original homeland and fear and hatred of the Bolshevik Soviet Union stayed with her all her life.