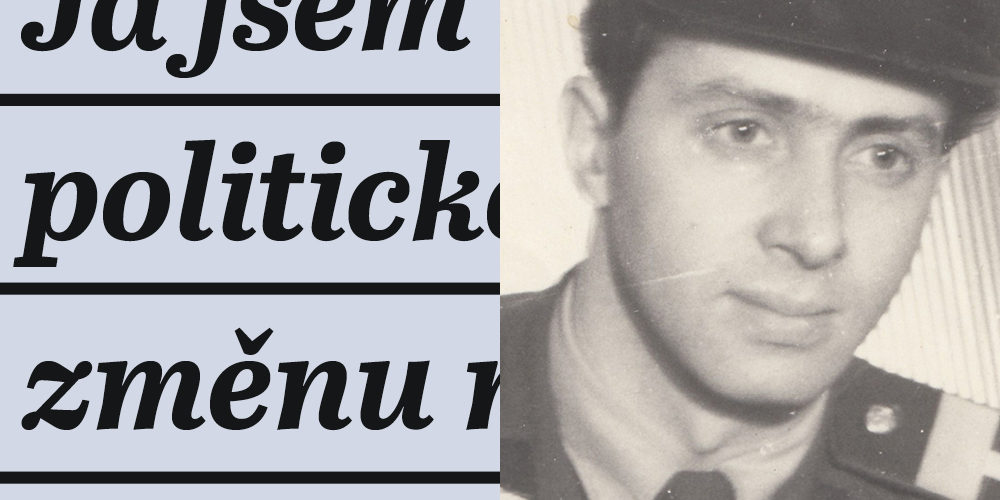

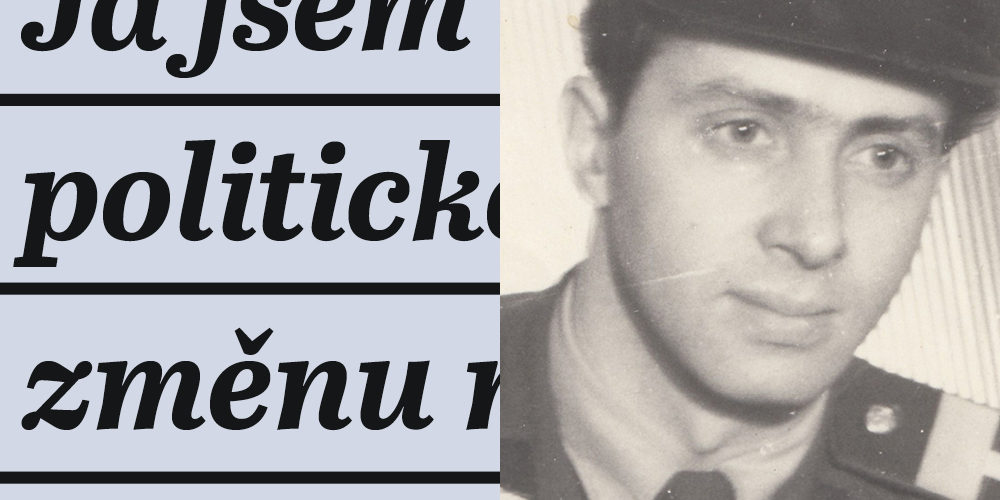

Milan Richter, a 20-year-old laborer, entered basic military service in 1954. He signed up for the army for life. He joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and served as a border guard on the border with what was then West Germany. In this role, he also experienced the loosening up of the situation in 1968 and the subsequent invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies. He accepted the interpretation of the impending counter-revolution dictated by the Soviet occupiers.

Although Milan Richter welcomed the rise of the Soviet reformist Gorbachev and admits that the border regime should have been relaxed sooner, he did not take the collapse of the communist regime in Czechoslovakia well. He did not want to serve in the army under the new conditions and retired. He resented the influence of foreign capital and the alleged selling off of national wealth. He argues against it by saying that the Soviet army, which had to leave Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s, did not take any property. But in doing so, he ignores, for example, the enormous ecological damage left by the Soviet occupiers, the consequences of which we are still dealing with today. “Does anyone know a greater totalitarianism than the totalitarianism of money?” he asks rhetorically, naming four certainties he believes the communist regime was able to provide: “to eat, to drink, to be clothed, and to live.”

He is still involved in the Czech Borderland Club. In his opinion, the role of border guards is not properly appreciated. “The truth will eventually come through, even if generations pass in the meantime,” says Milan Richter: “A state that does not guard its borders is not a state.”

Departure

In the 1980s, communist regimes were collapsing economically and socially. Falling behind the free world could no longer be disguised, and citizens invoked their rights. Rumors of change were coming from the Soviet Union in the era of Mikhail Gorbachev. Our country had been ruled for a second decade by the same set of normalization apparatchiks, who until then had devotedly listened to their comrades from Moscow, but did not want to hear about so-called perestroika – reconstruction.

When the totalitarian regime in our country began to collapse in November and December 1989 under the enormous onslaught of civil unrest, almost 80,000 Soviet soldiers, on whose threat the local regime relied, remained in the barracks – they were ordered not to intervene. In February 1990, the new president, Václav Havel, arrived in Moscow for an official visit. The Soviets apologized for the occupation in August 1968, and the foreign ministers concluded an agreement on the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Czechoslovakia. The negotiations were attended by the MP and musician Michael Kocáb. On 24 June 1991, to celebrate the event, he organized a concert with his band Pražský výběr in Prague’s Sport Hall, with the world-famous rocker Frank Zappa as a guest, and the whole show ended with the symbolic departure of a dummy of a Soviet soldier in a helicopter. Three days later, the real “last Soviet soldier,” Eduard Arkadyevich Vorobyov, the commander of the Central Group, left our country. In total, 73,500 Soviet soldiers, 39,000 of their family members, 1,220 tanks, 2,500 infantry combat vehicles, 105 aircraft, 175 helicopters and 95,000 tons of ammunition left Czechoslovakia.