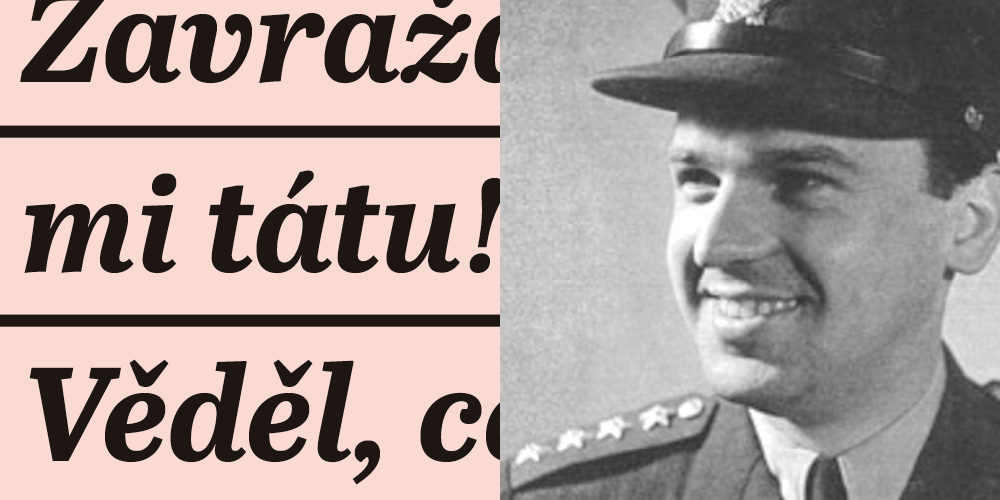

During World War II, Milan Píka served in the British RAF in an administrative position. He asked in vain to be reassigned to the Eastern Front. He hoped to find himself, gun in hand, next to his father – Heliodor Píka. Thousands of Czechoslovaks owed their lives to him: as a military attaché in the USSR, he negotiated their release from Soviet concentration camps – gulags – and their enlistment into the Czechoslovak unit forming in Buzuluk.

After the war, Heliodor Píka was deputy chief of the general staff and suffering from gall bladder pains. He used the leave in March 1948, which his comrades had ordered him to take, to undergo an operation. When he was arrested by secret agents, they pulled him from his hospital bed. There was a wound on his abdomen that had not yet healed. The investigation of the man, absurdly accused of treason, took place on 11 Dělostřelecká Street, where the Soviet secret service SMERSH was based after the war.

Milan and a few friends mulled over the possibilities of freeing his father. In November 1948, the secret police came for him and imprisoned him in Pankrác, where, coincidentally, his father was also imprisoned at the time. Heliodor had a cell with a window facing the courtyard. During the prison calisthenics, Milan would shout instructions to his cell mates so that his father could hear him:

“Keep your head up! Stay strong!”

Shortly before his execution, he sent him a message: “My dearest. (…) You can’t imagine what you were to me. A star, a ray of brightness,” Heliodor Píka wrote on death row in 1949.

After his father’s execution, Milan Píka was discharged from the army. He moved to Slovakia. Thanks to him, Heliodor Píka’s farewell letter has been preserved: “This is not a legal mistake, it is so clear – it is a political murder. (…) There is no anger, hatred or vindictiveness in me (…) However, I feel a bitter regret that justice, truth – perhaps only temporarily – has disappeared, and hatred and vindictiveness have spread, any sense of tolerance has disappeared…”